The Russian factor

If you then consider the tensions between the US and key Nato ally Turkey, which has recently been pursuing a partial tilt towards Moscow.

Now mix in the implications of the new government in Rome, which again has some curious attitudes towards Russia.

Then add the worrying schism within Europe between the "traditional" liberal democracies of the West and the increasingly harsh tones of "the populist democracies" of the East and you get a picture of an alliance riven with tensions.

This is before one even begins to talk about Nato's core business - the collective defence of its members.

Some certainly overstate the nature of Russia's military threat to the West, but a threat of some kind is real enough.

Indeed, it may be less from Russian tank armies as of old and more to do with cyber-influence, information operations and propaganda war.

But it is a battle that has already been joined and - despite President Vladimir Putin's recent benevolent sounding statements directed at the EU - many will choose to judge Russia by its actions rather than its words.

Nonetheless, the precise nature of this Russian challenge and what Nato collectively must do to meet it also divides the alliance.

Countries like Poland and the Baltic Republics, with a very different historical relationship with Moscow, see a much more immediate threat than other Nato allies.

A trial balloon from the Polish ministry of defence asking for the deployment of a permanently-based US division on Polish soil seems to fly in the face of existing Nato policy and suggests that some at least in Warsaw are not convinced that the alliance's current approach is sufficient.

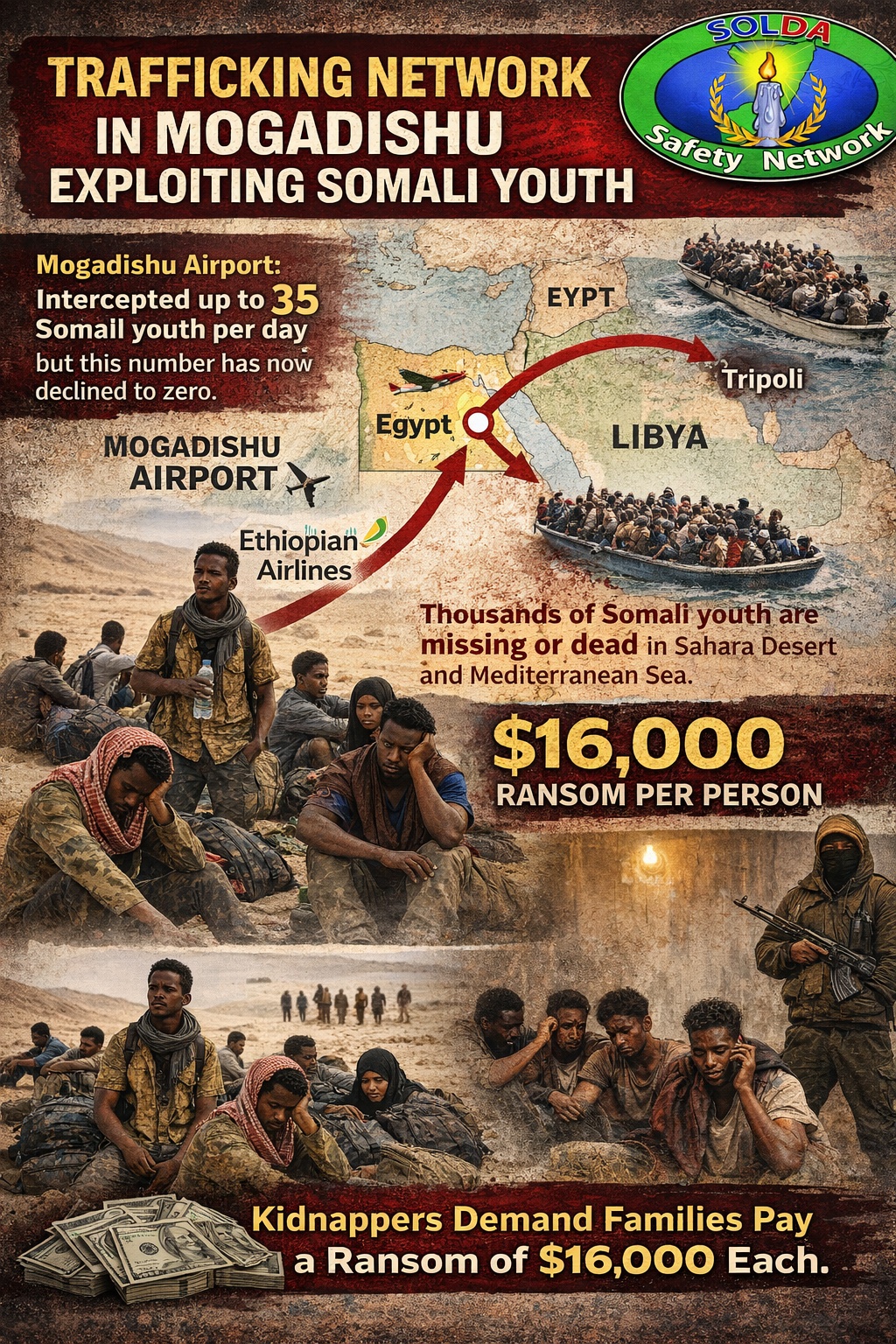

Those allies bordering the Mediterranean in Nato's south worry about Russia, But their biggest security threat remains the influx of people and instability from the Middle East and Africa - population movements which are becoming a key driver of political developments in a number of Nato countries.

The 'four 30s' plan

Either way, the summit will focus a good deal on "strength in depth", which makes a catchy slogan, but what does it really mean?

There's talk of Nato leaders agreeing to a new formula - "the four 30s" - a plan to be able to muster 30 mechanised battalions, 30 air force squadrons and 30 major warships within 30 days of the outbreak of any crisis.

But is this timeline really serious? Might it be too slow?

And given the lamentable readiness of Germany's armed forces for example, on paper one of the strongest countries in the Alliance, are such goals attainable or simply an aspiration?

Much also needs to be done to improve Nato's logistical support structure. For example, a key petroleum pipeline only extends as far as the old Cold War border between East and West Germany at the Fulda Gap.

Governments manage to employ a peculiar schizophrenia in the international system. Some might call it compartmentalisation. They agree in one forum whilst being at daggers drawn in another.

You will hear all sorts of statements that Nato is in rude health and busily adapting to the new challenges it faces.

In part this is true - at least in terms of the professional military and civil service. But no amount of spin can cover up the wider and multiple crises in the Nato family.

Pouring some balm on these tensions is what you would expect from a "normal" Nato summit and a "normal" US administration.

Is Mr Trump up to the task?

We will find out in a little over a month's time.

0

0

Nato's painful homecoming

Nato's painful homecoming