الترجمة العربية (Arabic translation)

ALEXANDRIA, Egypt – At around 2 a.m. on Saturday, April 9, a large blue fishing boat carrying hundreds of African migrants and their children capsized just off the coast of Egypt.

Some drowned quickly. Others thrashed in the water, yelling for help in Arabic, Somali or Afan Oromo. The few with lifejackets blew whistles that pierced through the shrieks.

A solitary electric torch probed the moonless darkness. It came from a smaller boat that was circling, tantalisingly close. The men on that boat, the people-smugglers who had brought their human cargo to this point, were searching only for their comrades. They ignored the screams of the migrants and beat some back into the water.

Just 10 migrants managed to scramble up into the smaller boat to join the smugglers and 27 other migrants already aboard.

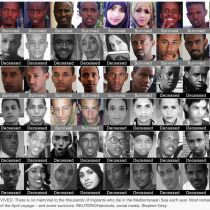

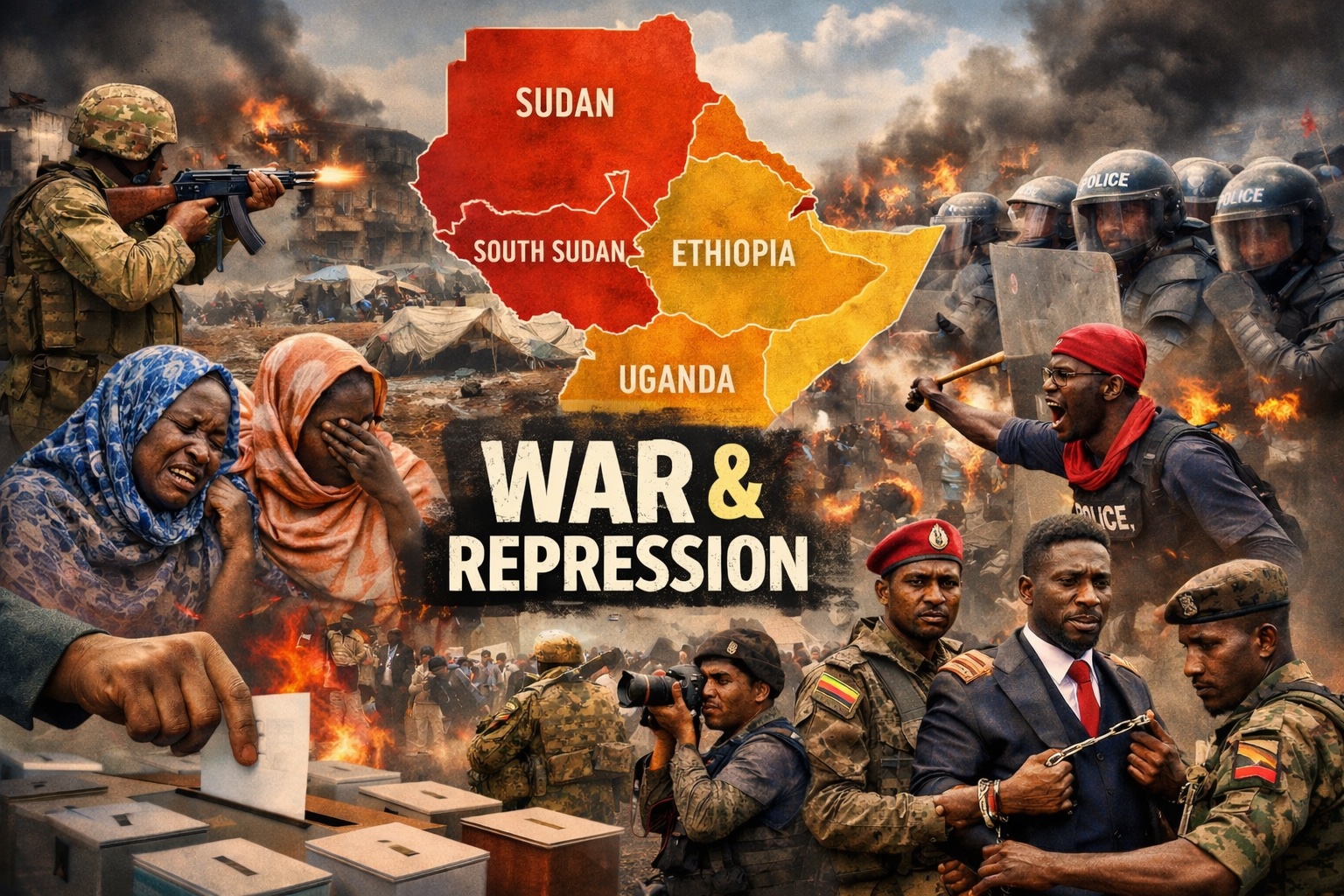

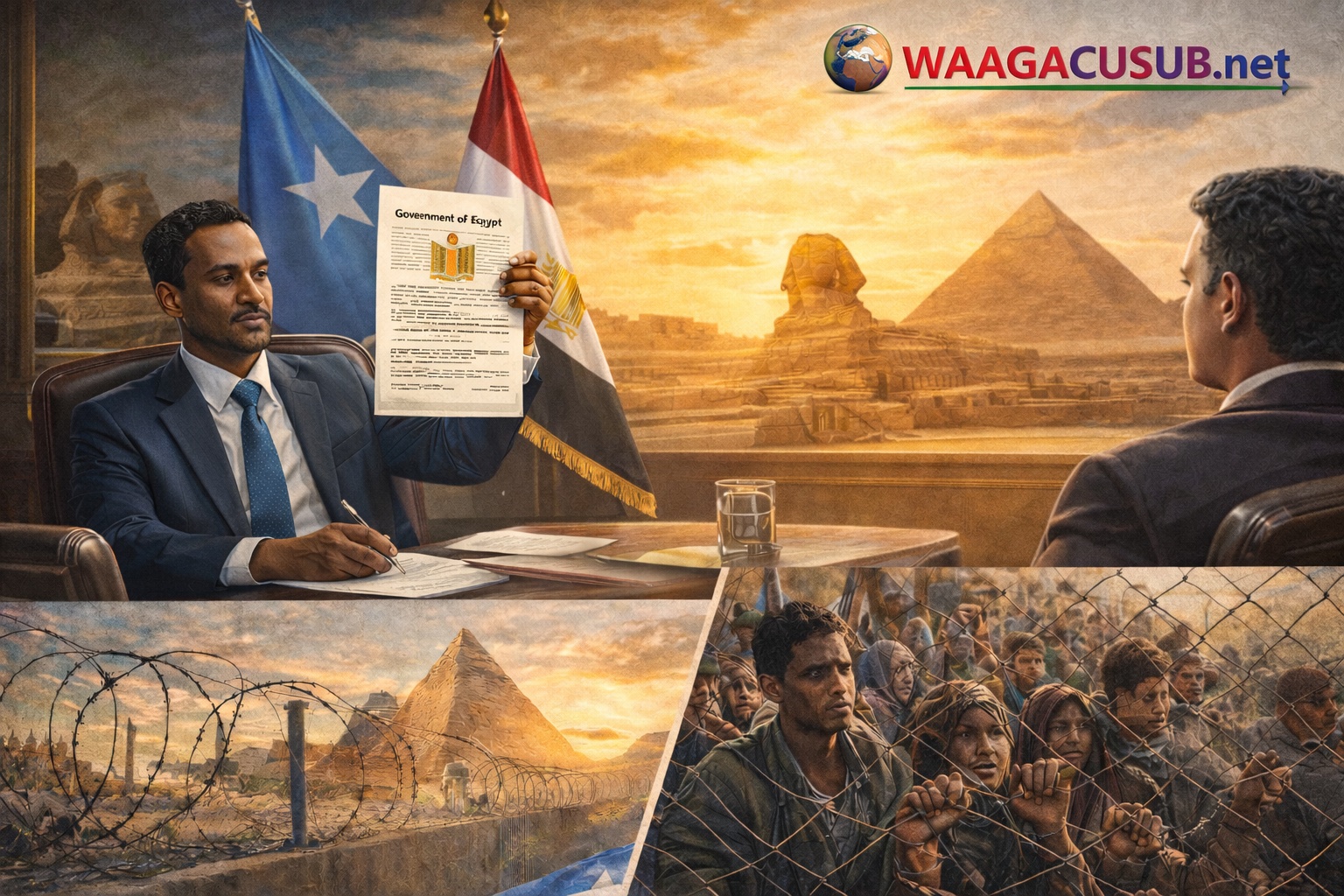

Around 500 adults and children died on the voyage, according to survivor and official estimates, the largest loss of life in the Mediterranean in 2016. Among the dead were an estimated 190 Somalis, around 150 Ethiopians, 80 Egyptians, and some 85 people from Sudan, Syria and other countries. Thirty-seven migrants survived.

Awale Sandhool, a 23-year-old who worked at a radio station in Mogadishu and had fled death threats at home, was among the few who swam to safety. Amid the chaos of the sinking, he said, his childhood friend Bilal Milyare had shouted to him from the water before drowning: "Could we not have been saved?”

Until now, no one has tried to answer that question.

A Reuters investigation in collaboration with BBC Newsnight has found that in the seven months since the mass drowning, no official body, national or multinational, has held anyone to account for the deaths or even opened an inquiry into the shipwreck.

When the news emerged via social media eight days after the sinking, European politicians showed brief interest. Italian President Sergio Mattarella suggested that the world should reflect on "yet another tragedy in the Mediterranean.”

But Italy, where the ship was headed, has not investigated the sinking. Nor has Greece, where the survivors landed, or Egypt, from where the migrants and smugglers set sail. There has been no investigation by any United Nations body, the European Union’s frontier agency, the EU police agency, any maritime agency, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, or the EU naval task force in the Mediterranean.

The only significant official action taken so far has been a fraud case against some of the smugglers in Egypt, sparked by complaints to police by a handful of grieving parents. No one has been apprehended in that case.

Reuters has identified the owners of the doomed ship and the ringleaders of the voyage, as well as the people-brokers who assembled the migrants in Cairo and Alexandria and took their money.

The investigation demonstrates the gaps in international law enforcement that make it easy for human smugglers to pursue their deadly trade in the Mediterranean. But it also shows what could be done if authorities chose to make a priority of investigating migrant deaths.

The official indifference to the disaster contrasts with how nations mobilised after EgyptAir Flight MS804 crashed in the Mediterranean on May 19, killing 66 people. Within hours of the crash, Egypt dispatched warships and air force planes to search for wreckage and survivors. France, Britain and the United States sent their own ships and aircraft. An investigation into what caused the crash and who was responsible continues in both Egypt and France.

0

0

Somalia: The forgotten shipwreck -500 people on this boat to be murder

The single biggest loss of life in the Mediterranean this year shows how authorities in Europe and elsewhere routinely allow those behind migrant deaths to get away with it.